Eight Days in Munich - Part 3

- Karl Koerber

- Dec 26, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Dec 26, 2024

We interrupted our stay in Munich with a twelve-day odyssey through the Austrian Alps and southern Germany. Reinhardt, bless his heart, insisted we take his Mercedes rather than renting a car. Our wanderings took us through the Austrian Tyrol and on to Lake Constance, the Black Forest, Freiburg, and a side trip to Strasbourg, before ending up in the Neckar Valley, home to more German relatives from both sides of my family.

There were some touching moments with my Uncle Karl, whose wife Maria had only recently died, and my Aunt Inge, sister of Reinhardt and my mother. Most of their children and grandchildren also lived in the area; much beer and good food was consumed in the process of becoming reacquainted with my, by now, substantial family in the Heidelberg area.

It was moving, for me, to spend time in Neckarsteinach, the town of my birth, and to see the house where I was born and lived the first two years of my life. We spent a few days wandering through this beautiful scenic area, with its forests and castles conjuring images from the Märchen: the fairy tales of the brothers Grimm and others that I learned in my childhood. The landscapes here are imbued with a long, rich history, into which the stories of my own family and ancestors are interwoven.

We got back to Munich just in time for the bacchanalian extravaganza of Oktoberfest. It was our good fortune to be gifted tickets to the opening day by our cousin, and so we were able to participate in this annual celebration of beer and Bavaria—a party that started as a regional festival but now attracts about six million visitors every fall. I allowed myself to get caught up in the atmosphere: drinking too much beer and standing on my chair while dancing and singing along to “Rosamunde” and Neil Diamond’s “Sweet Caroline”—songs to which everyone in our “tent” seemed to know the lyrics.

After the Oktoberfest hangover, our time in Munich was drawing to an end. I still wanted to visit Nuremberg, a city of deep significance to the Nazis and, fittingly, the site of the post-war prosecutions of Nazi criminals, so we borrowed the Mercedes one last time and flew north on the A9 autobahn, speeding through the flat Bavarian farmland and industrial areas. We didn't realize it at the time, but our route took us quite close to Dachau, the notorious site of the Nazis’ first and longest-running concentration camp. I would have liked to visit the museum there but, unfortunately, our time had run out.

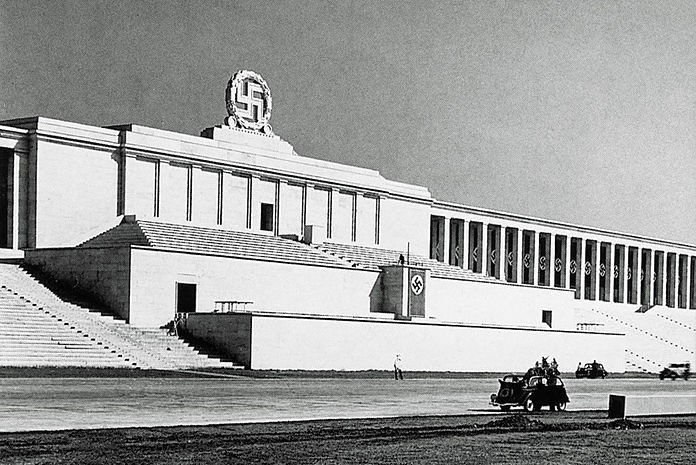

Our first stop in Nuremberg was the Documentation Centre, situated on the site where the Nazis held their now infamous Party rallies from 1933 through 1938. The museum is in a wing of the Congress Hall, an unfinished edifice designed by architects Ludwig and Franz Ruff that, had it been completed, would have been twice the size of Rome’s coliseum and held up to 50,000 for Nazi meetings. We parked, stretched, and then climbed the staircase that led to the museum’s entrance.

The permanent exhibit, Fascination and Terror, tells the story of the Nazis’ rise and fall, and the role that Nuremberg played in Hitler’s messianic vision. We picked up our audio guides and meandered through the various chambers and displays.

I knew the history fairly well, but, as I walked through the darkness of the galleries, the reality of the death, destruction and suffering wrought by Hitler and his Nazi cronies was brought home by the multitude of photographs, ephemera and artifacts glowing in illuminated panels along the walls. Ghosts everywhere.

We gathered on the observation deck that overlooked the cavernous amphitheatre that would have been the great hall. Here Hitler had hoped to address his acolytes in their thousands; now a few small trees and shrubs grew half-heartedly through cracks in the uneven pavement: an unkempt desolation that mocked the Nazis’ dream of Nuremberg as the glorious Romanesque capital of their movement. I sensed the ghost, glowering darkly as he drifted through the neglected monument that was now nothing but a sad reminder of his failure and shame.

As we emerged from the museum, we entered the park that surrounds the Dutzendteich, a small lake around which other reminders of the former Nazi presence are oriented. After a short walk along the towering back wall of the Congress Hall we stepped onto a creation of Nazi architect Albert Speer: the sixty-metre wide, one-and-a-half kilometre long, perfectly level Great Avenue, paved with 60,000 one-metre-square granite slabs. Speer aligned the avenue with Nuremberg’s Imperial castle—a symbolic link with the Germanic past that held a nostalgic fascination for Hitler and the Nazis.

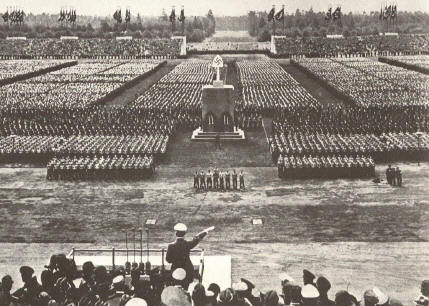

A walkway along the shore of the lake led us to the last stop on our tour of the grounds: Zeppelin Field, site of those massive outdoor rallies with tens of thousands of frenzied party faithful roaring their approval every time their Führer paused for breath during his animated address. The hulking body of the grandstand from which Hitler addressed the faithful still stands, but the Allies demolished the enormous swastika crowning the edifice in 1945.

I couldn’t resist the temptation. I stood on the rostrum where Hitler once looked out over the masses gathered to hear him speak. It was eerie—creepy, even—knowing that the architect of such evil had, not that many decades ago, occupied the exact space where I stood. I stepped off quickly, feeling like I’d slipped into a time-warp—a shadowy dimension where hollow-eyed ghosts languish in a tormented afterlife.

In the more recent past, the field has been the venue for rock concerts, rather than political meetings of the Nazi Party Congress. Bob Dylan and Eric Clapton played a double bill here in 1978. The Rolling Stones, U2, Bon Jovi and Bryan Adams also had concerts here, among many others—rehabilitating, perhaps, the space that once served as an arena for Nazis to rally around Adolf Hitler’s bigoted, supremacist ideology.

The hours had slipped by, but we were able to squeeze in one last stop in Nuremberg. I wanted to see Nuremberg Castle, a historic symbol of Germany’s imperial past that was integral to Nazi propaganda. We drove through the city, following the directions of what we came to know as “the lady,” who spoke to us in German from the GPS in Reinhardt’s car. Once we’d found a parking spot not too far from the castle, we had just enough time for a quick walkabout before we had to head back to Munich. In the stamp collection my father handed down to me, there's a commemorative stamp issued by the Nazis that shows the castle, with the inscription: Reichsparteitag 1934 Nürnberg - 1934 Nuremberg Reich Party Conference.

I managed to snap a photo from a similar angle as portrayed on the stamp and, from the castle's courtyard, captured a view of old Nuremberg's rooftops, looking, I suspect, much as they have for centuries.

Two days later, were on the flight from Amsterdam back to Calgary, and my journey of reconnection with my German family and my German heritage was over. I can’t claim to be an enthusiastic traveler, so I’m not certain that I would ever have made the trip if I hadn’t become so deeply engaged in examining my roots while I was researching and writing my book Through the Whirlpool. During that voyage of discovery, I had to confront the fact that some members of my family, just like millions of Germans from my parents’ and grandparents’ generations, were involved with Nazism. Some were Party members, some were sympathisers or “fellow travelers,” others just stood by, paralysed by indifference or fear, as the Nazis executed their racist agenda.

I suppose that traveling back to the land of my birth helped make it real. I walked on the cobblestone sidewalks of the town where I was born. I saw the Reichstag in Berlin, where the Nazis dismantled Germany’s fragile new democracy and catapulted themselves to absolute power in just a few short years. But I also saw the new, united, rebuilt Germany and touched the remnants of the Wall, now a mural gallery, that had divided the nation and its people for so long. I saw the effort the country has made to acknowledge the suffering caused by Adolf Hitler and his National Socialist government: the museums and monuments dedicated to keeping the truth of the Holocaust and other Nazi crimes in the public eye.

In sharing meals and walks and raising many a glass with my uncles, aunts and cousins, some of whom I only met for the first time, I was reassured that, for my family, at least, the ghosts of the Nazi past had been dispelled, and the wounds healed over.

Today, though, the generous and optimistic mood we encountered when we arrived in Munich alongside a million Syrian refugees in 2015 has soured, and I find it worrisome to watch a new tide of populism, fueled by fear, resentment and discontent, rising in Europe, America and around the world. The spectre of another cataclysm, this time much worse than what was unleashed by Hitler in 1940, looms just over the horizon, unless we can collectively come to our senses. Can we learn to put cooperation ahead of conflict, and turn the pledge “never again” into something more than the hollow phrase that the relentless stream of conflict, genocide and ethnic violence occurring in the intervening decades has made it? I hope so.

"At the end of the day, we must go forward with hope

and not backward by fear and division."

-Jesse Jackson

If you'd like to receive an email notification of a new post, you can subscribe here.

Always feel free to share!

Gerry:

A chilling reminder of the horrors the Nazis wrought and the scary notion that we may be looking down the gun barel of it happening again. And it won't be long before we find out if evil repeats itself. Thanks for the reminder Karl. Sad to say, it's well and truly needed.

Gerry Warner

I visited Dachau in late December 1966 and that visit is still etched in my memory all these decades later. At that time, few details were widely known about the horrors of the concentration camps and my 20 year old self was truly shocked.